Thursday, December 31, 2015

Monopolies Don't Go On Forever

Kodak believed its brand was so strong that they were impervious to competition. They turned down the opportunity to become an official sponsor at the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles. This gave competitor Fujifilm, a company looking for a foothold in the American market, the chance they needed to increase their market share. This missed opportunity by Kodak gave Fujifilm the push it needed to sustain its U.S. business and to overtake Kodak. Other factors that took Kodak down was a failure to continue creating new products, a culture of complacency, and a belief that the good times would never end.

In 1981, a Kodak executive named Vince Barabba completed a study that pointed to digital as being a real threat to Kodak's existing business model. But, on the bright side, Barabba said that the company had 10 years until digital technologies would become a viable threat. So what did Kodak do? Not much. The company was actually a pioneer in the field of digital photography, producing a prototype digital camera in December of 1975. But Kodak's huge margins on photography supplies, which reached up to 70%, were too enticing. The company commissioned many products that were "digital props" for its core physical film business, such as the Advantix camera. As other companies like Canon overtook them, the complacency of Kodak's leadership caused the company to fall to where it is now: a bit player in a commoditized industry.

Monday, December 28, 2015

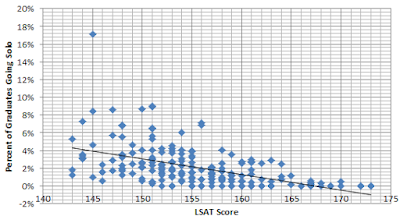

Tracking the dramatic decline of LSAT scores at the 25th percentile for incoming law school classes, 2010-2015.

The charts below show the distribution of changes in scores at the 25th percentile for classes entering law school between 2010 and 2015 and the number of schools where the 25th percentile score dipped below 150. [1] I also list the schools that lowered their 25th percentile score by four points or more during that period, a dispiritingly long list. I assume that this data will be published shortly at Law School Transparency, but I wanted to get it out there as soon as possible given that the application season is in full swing.

I note specifically the staggering 10-point LSAT decline experienced by Brooklyn Law School (BLS) at the 25th percentile, placing it in a two-way tie for the steepest decline of any law school in the country. BLS Dean Nicholas Allard has led the effort to place the blame for falling bar passage rates on Moeser and the NCBE, rather than on law school admissions practices. Allard’s noxious fog of bluster and accusations can be dispelled with the following three words: "Ten point decline."

A few years ago, Paul Campos wrote a book called "Don’t Go to Law School (Unless)." A possible alternate title for this blog post might be "If You Must Go to Law School, For God’s Sake Don’t Go to ( )." "( )" would include the vast majority of those schools that reacted to the dropoff in applicants by substantially lowering their admissions standards, especially those where the admissions standards were pretty low to begin with. The Deans and unprotesting tenured faculty at these schools have displayed a level of greed, recklessness, and contempt unworthy of professionals.

Wednesday, December 23, 2015

Indiana Tech tries to appear selective, Part 2

Indiana Tech turns out to have a reason for this move: ABA accreditation. According to scam-dean Cercone, the ABA intimated that Indiana Tech was insufficiently selective: its "admission standards going forward needed to be more in line with standards for other new law schools". Cercone concluded that a "stronger … student profile" would favor accreditation.

But Indiana Tech cannot bet the farm on a three-point increase in median LSAT score. Right after its failed bid for accreditation, it brought in a scamster named John Nussbaumer as its "new Associate Dean for ABA Accreditation and Bar Preparation". Nussbaumer went to Indiana Tech with "31 years of full-time faculty experience at Western Michigan University Thomas M. Cooley School of Law, including 18 years in senior academic leadership positions".

Now, Nussbaumer wasn't hired for his ability to dot every i and cross every t on the application. No, two other notable factors got him lured away from his sinecure at Cooley. First, he has experience in winning accreditation for other law schools: "[h]e has appeared more than a dozen times before the ABA Accreditation Committee and Council of Legal Education, helping lead successful efforts to secure provisional and full approval for three different law school branch campuses" (presumably a reference to Cooley). Second, and undoubtedly more important, he is an insider in the ABA accreditation scam:

He has served as a member of the ABA Section of Legal Education Diversity Committee, and he is currently a fact-finder and site inspection team member for the ABA Accreditation Committee. He has worked collaboratively on accreditation issues with the staff of the ABA Managing Director’s Office, including Managing Director Barry Currier, and has also worked on accreditation issues with the ABA House of Delegates, the ABA Standards Review Committee, the U.S. Department of Education, and the Congressional Black, Hispanic, Asian Pacific, and Progressive Caucuses.With its hired gun Nussbaumer, Indiana Tech can be expected to—ahem—procure accreditation just in time for the graduation of its inaugural class. But how much is this costing the parent university?

A few years ago, when the building of this law school was announced, Indiana Tech University had a $40M endowment. I conservatively estimate outlays of $6M per year for the law school. (If the average salary is $100k and other charges such as benefits and payroll taxes add half of that, the 28 employees cost $4.2M per year.) Had the law school succeeded at bringing in 100 students in each class and maintaining its annual tuition at $30k, by now it would have been reaping $9M per year in income. Discounts on tuition would have reduced that figure, but the theoretical annual surplus of $3M could have made up for many discounts, shortfalls in enrollment, and other deficiencies.

In its first year, Indiana Tech was quite stingy with discounts. Only one person got half of tuition waived, and his "discount" actually exceeded tuition. (I'm willing to bet that he was Felts, the boy who on Indiana Tech's Web site posed in an unprofessional orange-yellow necktie and announced that people should "certainly" attend Indiana Tech on the advice of a local judge—without mentioning the significant fact that that judge happened to be his father.) So probably the people who approved the establishment of the law school calculated that the thing would break even at 75 students per year (¾ of the anticipated 100), maybe even fewer, and that in any event the university would cover any shortfalls for the first five or six years.

Instead, total enrollment has not yet come close to the figure anticipated for the first class alone, and tuition is now at zero. The university must be covering just about the entire cost of operating its toilet law school—not to mention the cost of two bids for ABA accreditation. That's one hell of a drain on an endowment that several years ago stood at $40M. And the rest of the university depends on that endowment, too.

On top of all that, the university now has to pay for an "Associate Dean for ABA Accreditation and Bar Preparation" who was approaching retirement from a cushy job at Cooley. For how long can the university afford to sustain its financial sinkhole of a law school? The endowment must be badly depleted, and the law school won't be viable even if (rather, when) it becomes accredited. Expect this toilet to be flushed once and for all within two or three years.

Thanks to Dybbuk for much of the information that inspired today's article.

Sunday, December 20, 2015

Indiana Tech tries to appear selective

http://law.indianatech.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2015/12/Std-509-InfoReport-2015.pdf

Recall that Indiana Tech eliminated tuition this year (although the 509 report above does not show that fact) and that this past summer it announced the hope that 20 people would enroll in first year. Why did Indiana Tech miss that target? Did too few people apply?

No: Indiana Tech got 99 applicants. Yet it accepted only 31! What was wrong with the other 68 applicants? Were they all so unspeakably horrible that Indiana Tech, where 143 is a "serviceable" LSAT score, couldn't possibly consider them?

To answer those questions, compare this year's 509 report to last year's:

http://law.indianatech.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2015/09/2014-Rule-509-Report.pdf

In particular, look at the following data:

Admissions:

2015: 99 applicants, 31 were offered admission, 13 matriculated

2014: 96 applicants, 78 were offered admission, 35 matriculated

Undergraduate GPAs (75th, 50th, and 25th percentiles):

2015: 3.61, 3.42. 2.99

2014: 3.15, 2.85, 2.49

LSAT scores (same percentiles):

2015: 153, 151, 148

2014: 151, 148, 142

A few observations:

The number of applicants in each year did not change significantly, but the rate of offers dropped from 81% in 2015 to 31% in 2014. In one short year, during which it failed to achieve accreditation, Indiana Tech went from open admissions to moderate selectiveness. That change is unprecedented.

Moreover, its GPAs shot up more than half a grade point, and its LSAT scores too increased dramatically. Only a few law schools avoided a drop in their median LSAT score. A three-point increase was rare indeed.

We can also reasonably infer that the calibre of Indiana Tech's applicants in general did not suddenly improve. The failure to achieve accreditation would have deterred most of the (ahem) better applicants. In addition, Indiana Tech would not have had to eliminate tuition if it had become a hot commodity.

Putting these facts and inferences together, we get the most likely conclusion: Indiana Tech rejected the bulk of its core audience—the dullards with the "serviceable" LSAT scores and GPAs—to come across as progressing in quality. By admitting only the best of its generally dreadful pool of applicants, Indiana Tech could manipulate its GPA and LSAT figures upwards. And why not? There was no cost to Indiana Tech: revenue was going to be exactly the same—nil—whether Indiana Tech admitted a baker's dozen of applicants or all 99.

Expect to see bullshit propaganda about "progress" and even "excellence" at Indiana Tech. But don't believe the hype.

Wednesday, December 16, 2015

The Oft-Ignored, Omnipresent Lawyer Glut

More below the fold.

Thursday, December 10, 2015

Indiana Tech lawprof andre douglas pond cummings writes fawning law journal article comparing a better-known fellow lawprof with hip hop musician Ice Cube

a. andre douglas pond cummings

- "When Professor Delgado published The Imperial Scholar, its impact was a literary shot across the bow of the traditional legal academy in its aggressive repudiation of entrenched White male civil rights legal scholarship. Like a hand grenade launched into the upper reaches of an ivory tower, Delgado authored a blistering critique that condemned famed civil rights scholars for their own racism and failure to garner, appreciate, or represent the views of the very oppressed minority groups on whose behalf these scholars purported to advocate." andre douglas pond cummings, Richard Delgado and Ice Cube: Brothers in Arms, 33 Law and Inequality: A Journal of Theory and Practice 321, 332 (2015).

- "From the movement’s inception, Critical Race theorists championed storytelling and narrative as valuable empirical proof of reality and the human experience, while rejecting traditional forms of legal studies, pedagogy, and various forms of civil rights leadership. Similarly, hip-hop, at its root, is narrative in form; the best, most recognizable hip-hop artists use storytelling as their most fundamental communicative method." Id. at 324.

- "[M]any CRT pioneers employed counterstories, parables, chronicles, and anecdotes aimed at revealing the contingency, cruelty, and self-serving nature of majoritarian rule. Similarly, hip-hop revolves around storytelling." Id. at 326.

- "The assault on the rear flanks [of the status quo] was the clarion call to every scholar of color and emerging outsider scholar and lawyer to a new and different conceptualization by which legal scholarship could be presented and legal practice conducted." Id. at 334.

- "Ice Cube, in the same narrative format championed by Richard Delgado, spun tales and stories in his rhymes." Id. at 338.

- "Professor Delgado and N.W.A./Ice Cube both expose and decry racism, inequality, and oppression with passion and explosiveness through deeply personal narrative." Id. at 339

- "Both Delgado and N.W.A. identify "the cure" to their detailed experiential ills as furious storytelling—Delgado in A Plea for Narrative and N.W.A. in Fuck tha Police and Gangsta Gangsta." Id.

- "Through narrative storytelling and funky bass lines, CRT and hip-hop seek to educate, inspire, and motivate a generation." Id. at 340.

- "When Professor Delgado’s influence is compared to that of Ice Cube, the hip-hop generation will understand the depth of this homage." Id. at 341.

Friday, December 4, 2015

LSAC Applicants Up 0.6% From This Time Last Year

|

| Sigh. Some people never learn. |

Friday, November 27, 2015

Truth In Advertising

During the 1980s and 1990s, public health officials the world over tried to figure out how to stem the popularity of cigarettes. In 1989, the New Zealand Department of Health’s Toxic Substances Board recommended plain packaging for tobacco products. This meant that tobacco products were to be sold solid color packs with a huge warning about the dangers of smoking displayed on the pack. As one can imagine, this proposal met with intense opposition from tobacco manufacturers and their lobbyists. A breakthrough was made when Australia passed the world's first plain packaging regulations in 2011. Researchers suggested that without the visual stimuli on the cigarette packs, cigarettes became less attractive. In an unexpected development, smokers also reported that cigarettes in plain packaging tasted worse. While there are no long term studies about the effects of plain packaging on smoking rates, the anecdotal data suggests that smoking rates are down.

Law school brochures sell a vision of rapturous success and opportunities to do work at the law's bleeding edge. The brochures lead the average student to believe that he or she will be assured of an upper middle class income while doing cutting edge legal work. Programs in esoteric fields like space law or hip-hop legal studies are trotted out in an attempt to show students that a legal education is a great way to break into almost any field. The possibilities are limitless for the law grad. These brochures massage employment numbers to the limit allowed by the ABA's recent employment data disclosure rules. That $180,000 in tuition for 3 years? A drop in the bucket when students consider the riches awaiting them after that J.D. diploma is in hand.

In recent years, the law school industrial complex has seen some waning in its revenue generating power. Law schools were led kicking and screaming to disclose employment statistics that did not appear to have been created by the Iraqi Ministry of Information. Graduates saddled with no job prospects and six figure debt are scattered across our country, unable to live the American Dream while crushed by their decision to study law. What is the response of the deans, professors and administrators? They point to the fact that unemployed graduates are lazy or not smart enough to get a job. If grads network and work for peanuts, they will eventually be able to create comfortable lives working as solo attorneys. Others say that law schools teach students "how to think". This ability to think should open doors for these grads, if only they would look for "JD advantage jobs". Something needs to be done.

Law schools need to be treated like the cigarette industry. There is no rational incentive for law schools to act in the best interests of their students. Law schools that do not provide positive job outcomes are defrauding not only the students, but the taxpayers as well. The enrollment numbers are dwindling, but there is still an oversupply of lawyers relative to what the market will bear. We need to take a tip from the plain packaging movement and advocate for the inclusion of large warnings on all law school brochures and glossies. The messages should say something like:

WARNING: DEBT ACCUMULATED FROM LAW SCHOOL CANNOT BE PAID OFF IF YOU DON"T WORK FOR A LARGE LAW FIRM

or

WARNING: LAW SCHOOL WILL NOT TEACH YOU HOW TO ACTUALLY PRACTICE LAW

This type of measure won't stop everyone who shouldn't go to law school from enrolling. There are special snowflakes out there blindly convinced of their future success no matter what evidence exists to the contrary. But, it should help students on the fence take pause and think twice. People can't be stopped from making bad decisions. But it is our duty to do all we can to make it as difficult as possible.

Tuesday, November 24, 2015

Did the 79 law school deans who challenged NCBE Chief Erica Moeser’s “less able” explanation for falling bar passage rates lower admission standards at their own schools?

"We, the undersigned law school deans, respectfully request that the National Conference of Bar Examiners facilitate a thorough investigation of the administration and scoring of the July 2014 bar exam. .. . . In particular, the investigation should examine the integrity and fairness of the July 2014 exam. We also request that the NCBE provide the evidence it relied on in making the statement that the takers of the bar exam in July 2014 were less able than those in 2013." – Memo to NCBE, Chief Erica Moeser, signed by 79 law school Deans.

"Your unexpected defense of your test goes on to conclude that that the serious drop in scores was due to, in your view, the 2014 test takers being "less able" than the 2013 test takers. We don't know what evidence you have to support this surprising (and surprisingly disparaging) claim, but we do have evidence about our own 2014 graduates, and it tells our precisely the opposite: their credentials were every bit as good as our 2013 graduates, if not better. . . . In plain language, I disagree with you: It's not the students, it's the test."

increased

|

12

|

|

unchanged

|

26

|

|

down by 1 pt.

|

26

|

|

down by 2 pts.

|

11

|

|

down by 3 pts.

|

3

|

UC-Hastings, Charleston, Colorado

|

down by 4 pts.

|

1

|

Case Western

|

increased

|

3

|

|

unchanged

|

3

|

|

down by 1 pt.

|

5

|

|

down by 2 pts.

|

12

|

|

down by 3 pts.

|

12

|

|

down by 4 pts.

|

13

|

|

down by 5 pts.

|

16

|

|

down by 6 pts.

|

5

|

American, Capital, Faulkner, LaVerne, Valparasio

|

down by 7 pts.

|

4

|

McGeorge, Vermont, Southern Ill., Whittier

|

down by 8 pts.

|

4

|

Ave Marie, Charleston, Thomas Jefferson, Cooley

|

down by 9 pts.

|

2

|

Brooklyn, Hofstra

|

As for Brooklyn Law, its 25th percentile score and median LSAT declined between 2010 and 2011. So did its 25th percentile and median GPA. Thus, Allard’s claim that he had "evidence"-- the nature of which he did not disclose-- to establish that the credentials of BLS’s 2014 graduates "were every bit as good as our 2013 graduates, if not better" may have crossed that thin line that separates self-serving bullshit from filthy lie.

Friday, November 13, 2015

Seattle Law Prof. Paula Lustbader promotes civility training in Tuscany

Dubious too, perhaps, is Lustbader's role in co-founding and directing Seattle Law’s Access Admissions program, through which the law school admits students "whose capabilities may not be accurately reflected in GPAs and LSAT scores." Perhaps their legal capabilities are better expressed by their mastery of the triple heel click.

The Robert’s Fund has held its CLE program in Sovana several times since 2011, with the next such program ("The Civility Promise in Tuscany") scheduled for April, 2017. The cost is $3,650 (standard room) to $3,950 (deluxe room at four-star hotel) for early bird registrants, and $1,650 to $1,850 for one’s room-sharing spouse or significant other. The six-member faculty includes Lustbader, two Italian judges (one retired), and one, uh, artist in residence. The Robert’s Fund’s listed "staff and consultants" include four Seattle U. lawprofs (one emeritus), one University of Washington lawprof, and one Hamline lawprof.

"Revitalize your commitment to the profession you love. . . This popular seminar convenes in Sovana, a charming medieval village surrounded by verdant vineyards and lush olive groves. In this peaceful setting, participants immerse themselves in a continuing education program that integrates lectures, discussions, and interactive exercises that focus on fostering civility in the legal profession. The seminar is complemented by guided excursions through the nearby villages and beautiful countryside.. . . Enrich your personal and professional life. Relax and reconnect with yourself... Develop and deepen relationships... Engage in thought-provoking dialogue… All this while earning 30 CLE/CJE credits (including 8 ethics credits)."The Robert’s Fund website includes nine brief video testimonials from past participants of the Tuscany civility program (one of whom (Craig Sims) is now a member of the faculty of the program). They make for entertaining viewing. All are predictably enthusiastic, but several express themselves so inarticulately about the nature and benefits of the program that it made me wonder whether too much international civility enrichment can have deleterious effects on one’s brain.

Saturday, November 7, 2015

"Hip Hop and the Law": Dougie Fresh's magnum opus

The celebrated André Douglas Pond "Dougie Fresh" Cummings and two other intellectual colossi of legal hackademia have co-edited Hip Hop and the Law, a compendium of the finest scholarshit in a field crucially important to bench and bar. Allow me to reproduce its promotional blurb:

"What is important to understanding American law? What is important to understanding hip hop? Wide swaths of renowned academics, practitioners, commentators, and performance artists have answered these two questions independently. And although understanding both depends upon the same intellectual enterprise, textual analysis of narrative storytelling, somehow their intersection has escaped critical reflection. Hip Hop and the Law merges the two cultural giants of law and rap music and demonstrates their relationship at the convergence of Legal Consciousness, Politics, Hip Hop Studies, and American Law. No matter what your role or level of experience with law or hip hop, this book is a sound resource for learning, discussing, and teaching the nuances of their relationship. Topics include Critical Race Theory, Crime and Justice, Mass Incarceration, Gender, and American Law: including Corporate Law, Intellectual Property, Constitutional Law, and Real Property Law."

Adam Lamparello—noted for his, er, personal revelations—recently hosted a reception for this world-historic publication. I am woefully sorry that I did not find out in time to attend. When shall I ever have another opportunity to get my very own copy of Hip Hop and the Law inscribed by Dougie Fresh, entirely in lower-case letters?

Practitioners, professors, and students should rush to Amazon.com and grab one (or more!) of the 19 available copies for the trifling price of $53, with free shipping. Learn how to apply the intersectionality of law and hip-hop to everything from Critical Race Theory™ to litigation over real property. Launch a new career in the dynamic field of Hip Hop Studies. Break new scholarly ground through critical reflection on this tragically neglected subject You need this book.

Tuesday, November 3, 2015

Law Deans warn that capping student loans threatens the "rule of law" and the "individuals and institutions in our society."

"Talented students are drawn to the legal profession because lawyers play a vital role serving individuals and institutions in our society. . .[C]utting federal loans will only narrow the pool of people who can pursue a legal career and decrease the availability of lawyers to serve this need." – letter to the editor of the New York Times by Law Dean Matthew Diller.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I fear a collapse into anarchy– the bad W.B. Yeats kind, not the good Noam Chomsky kind. Social collapse begins when the rule of law starts to fray, like a once-beautiful tapestry that has been damaged, or like the nerves of a put-upon law professor forced to explain for the umpteenth time how his or her scholarshit is a bargain at any price, even if that price is paid by debt-ridden law grads. And when even a normally beigist establishment newspaper like the New York Times boldly endorses the viewpoint of law-hating scamblog insurrectionists, you know that society is in peril.

The logic is cruel and irrefutable. If you tamper with the availability and amount of federal student loans then fewer people will be able or willing to attend law school. If fewer people attend law school, then there will obviously be fewer lawyers. Ours is a society of laws, so if the lawyer supply is disrupted, we will eventually lose the rule of law.

What follows are a few facts about the letter writers quoted above, and about the institutions they lead or led, which may be marginally relevant to assessing their interest, bias, and character. Might there be some reason, other than the obvious imperative to preserve society and the rule of law, why they want an unobstructed flow of money from taxpaying public into law school coffers via the ever-reliable conduit of gullible young persons’ ruined lives?

Kellye Testy, Dean of the University of Washington School of Law, was paid $375,012 in 2014. This was the 45th highest salary for a State of Washington employee. (Eight football coaches and three basketball coaches were paid more, proving that law school is far from the only scam out there). In an interview conducted in 2012, Testy rejected as "paternalistic" the suggestion that class size be reduced, though the school ultimately did decrease its class size very slightly (From 176 1Ls in 2012 to 163 in 2014). Testy is a strong proponent of Washington State’s limited license legal technician program, under which nonlawyers can engage in the "limited practice of law"– as long as they take 45 credit hours of paralegal instruction, plus additional coursework related to the particular area of law for which licensure is sought, from an ABA-accredited law school. Speaking of limited practice, Testy graduated from law school in 1991 and became a Professor of Law in 1992, with only a one-year long Seventh Circuit clerkship sandwiched between her law school graduation and her law school professorship.

Blake Morant was recently appointed Dean of George Washington Law School. In Fiscal 2012, Morant’s predecessor, Paul Schiff Berman, collected $519,280 in "reportable compensation" from GW and an additional $54,876 in "other compensation from the organization and related organizations." Thus, Morant's GW salary is probably higher than his $443,856 annual take as Dean of Wake Forest Law. Morant serves as President of the Association of American Law Schools. In his 2015 Presidential address, he declared that "[T]he need for quality legal education has never been more acute. The competitive global market requires professionals who can think critically and provide innovative solutions to complex problems." George Washington has the 7th highest percentage of ten-month-out "school-funded" jobs among the law schools (13.4%), suggesting that there are at least a few GW law grads having difficulty peddling their critical thinking wares in the global marketplace. The average law school debt of a GW Class of 2014 law grad was $141,246.

Matthew Diller was recently appointed Dean of Fordham Law (2015), having spent the preceding six years as Dean of Cardozo Law (2009-2015). The average law school debt of the members of the class of 2014 at Fordham and Cardozo was $140,577 and $121,644 respectively. Between 2010 and 2014, Cardozo’s LSAT for incoming students fell by five points at the 25th percentile and four points at the median, so at least Diller is sincere in his opposition to policies that would "narrow the pool of people who can pursue a legal career." Diller boasted to the New York Times that "Schools, including Fordham Law. . . have expanded scholarship aid," but there still may be room for improvement. Fordham ranked in the bottom half of law schools in terms of median tuition discount ($12,500) and percentage of students receiving discounts (49.1%). Diller’s predecessor as Fordham Law Dean, Michael M. Martin, was paid $543,108 in Fiscal 2013.

Judith Areen was a law school faculty member at Georgetown for 43 years, including 16 years as Dean or as interim dean (1989-2004, 2010). Georgetown Law has the worst non-funded law job placement record among the elite T14, which may be related somehow to its enrolling the largest entering class of any law school in the country. In 2015, Areen became executive director of the Association of American Law Schools (AALS), which "represents the deans and professors of 179 law schools" and which emphasizes the importance of legal scholarship within law schools. According to its most recent available 990, the AALS sits upon about 11 million dollars in net assets. It seems to derive most of its five million dollar annual revenue from law school faculty recruitment services. The AALS is known for hosting a huge annual five-day-long two million dollar "conference" that draws over 3,000 party-loving lawprofs from all over the country.Areen's predecessor as AALS executive director, Susan Westerberg Prager (who has since become Dean of bottom-tier Southwestern Law School), was paid $459,221 by AALS in Fiscal 2013.

In 2012, Areen stated that, "It’s law graduates who don’t practice law who are often most complimentary about their legal education and the analytic skills they received." At least she did not say that the rule of law depends on having an ample supply of nonpracticing lawyers.

Tuesday, October 27, 2015

Does the logo on your T-shirt reveal your aptitude for legal practice? Take the DiscoverLaw quiz.

But I admit that if a kid is thinking about law school, he or she ought to go one step further and consider what practice area he or she would like to specialize in. To make this determination, it is advisable that the kid takes stock of his or her own values, concerns, and goals.

So I was hopeful that the "Fields of Law" quiz on DiscoverLaw's website might prove a useful tool. A quiz-taker answers 18 multiple questions and then clicks the "find out" button to determine which practice area "just might be the field that’s right for you." The possibilities include civil rights, corporate and securities, criminal, entertainment, environmental and natural resources law, family and juvenile, health, intellectual property, international, sports, and tax.

http://www.discoverlaw.org/considering/quiz/

However, after reviewing the specific questions, I was not fully persuaded that this quiz really does reveal legal aptitudes. But judge for yourself:

1. My iPod is filled with ...

- legally downloaded music

- baseball highlight

- sounds of nature

- language lessons

- my favorite sports team

- a brand name

- my favorite band

- something from nature

- pollution

- disease

- plagiarism

- bye weeks

- save the planet

- fight crime

- help children

- work with celebrities

- attending a murder mystery dinner theater

- visiting an art museum

- dinner at a French restaurant

- volunteering at a Boys & Girls Club

- about heists and crime

- with subtitles

- that critique society

- that have a celebrity cast

(Although, looked at from a different perspective, DiscoverLaw has succeeded in designing a multiple choice test with no wrong answers-- you just have to remember to complete it. Perhaps that is a template for a redesigned multistate bar exam, one that would even satisfy the test's harshest critics, such as Brooklyn Dean Nicholas Allard, as well as those worthy strivers who have heretofore felt the sharpest sting of bar exam oppression, such as Infilaw's Arizona Summiteers).

I appreciate that the legal academy is slightly less scammy than a few years ago in certain respects. Most law schools have reduced class size, increased the availability of tuition discounts, and have been forced to become more transparent as to employment outcomes. However, in one major respect the scam is becoming dramatically worse– namely, the ever-increasing eagerness of law schools to recruit--I would even say entice--kids whose lack of academic credentials and social capital places them at severe risk of a disastrous outcome.

-------------------------------------------------------

notes:

[1] According to LSAC’s Form 990s (available at Charity Navigator) LSAC gave DiscoverLaw a grant of $54,731 in Fiscal 2013. LSAC gave DiscoverLaw a grant of $84,896 in Fiscal 2012. LSAC gave DiscoverLaw a grant of $56,429 in Fiscal 2011. DiscoverLaw’s address is the same as LSAC’s– 662 Penn Street, Newtown, PA, 18940.

[2] It is called DiscoverLaw-- there is no space between the "r" in "Discover" and the "L" in "Law." Credit to LSAC for making that extra effort to be obnoxious even when there is no apparent reason for it.

[3] But at least high school kids can't actually apply to law school, right? Not so fast. The recently published Report of the ABA Task Force on Financing Legal Education praises various "innovations" and "experiments" as "the source of possible solutions and models" (which an unsympathetic critic could interpret as meaning creative new ways to bamboozle the vulnerable). One such innovation that the Task Force singles out for praise is the following:

"The program at the Sturm College of Law even includes an option allowing highly qualified high school seniors to apply for its three-plus-three program as they apply to the university for undergraduate admission." (Report, p. 12)

Wednesday, October 21, 2015

Washburn and the Solo Sub-Scam

But it's hard to ignore some bold claims:

The law school ranked 24th nationally in employment in full-time, long-term jobs requiring bar passage, according to 2015 American Bar Association data — above all other law schools in Kansas, Colorado, Oklahoma, Texas and Arkansas.Lest you think this is just puffed-up journalism, when I went to the school's website, I found this rather loud banner:

“We are pleased that our graduates are among the nation’s most successful in securing full-time, long-term jobs that require bar passage. This is the gold standard of jobs for lawyers,” said Washburn law school dean Thomas R. Romig.

Twenty-fourth in the country sounds pretty impressive...until you look into the actual numbers. Let's look at Washburn's 509 data for the Class of 2014 (copied from LST):

| Employed | LTFT | LTPT | STFT | STPT | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solo | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 2-10 Attorneys | 29 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 32 |

| 11-25 Attorneys | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 26-50 Attorneys | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 51-100 Attorneys | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 101-250 Attorneys | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 251-500 Attorneys | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 501+ Attorneys | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Size Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Business & Industry | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| Government | 20 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 21 |

| Public Interest | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Federal Clerkships | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| State & Local Clerkships | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Other Clerkships | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Education | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Employer Type Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Employed Total | 91 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 97 |

So... 10 of their 91 "employed full time" graduates went solo. For their entire class of 112, that's almost 9% of their graduates. That's high. How high?

Fourth in the country high. Check out this list:

PERCENTAGE OF SOLOS TO GRADUATES

| LAW SCHOOL | SOLO % |

| Texas Southern University | 17.14% |

| Lincoln Memorial University | 15.56% |

| Willamette University | 9.02% |

| Washburn University | 8.93% |

| St. Mary's University | 8.72% |

| University of Massachusetts Dartmouth | 8.64% |

| Faulkner University | 8.43% |

| Southern University Law Center | 7.27% |

| Florida International University | 7.14% |

| John Marshall Law School - Atlanta | 6.84% |

| University of Nebraska | 6.84% |

| University of La Verne | 6.82% |

| University of Toledo | 6.50% |

| South Texas College of Law | 6.41% |

| Texas A&M | 6.03% |

| Mississippi College | 5.71% |

| University of Arkansas - Little Rock | 5.60% |

| Oklahoma City University | 5.56% |

| Charlotte School of Law | 5.33% |

| Liberty University | 5.26% |

I wonder if this is the esteemed company Washburn wants the public to see it associated with.

There are other problems with Washburn's claim regarding its stellar employment results, the most notable being that Washburn placed only 12.5% of its graduates in law firms of 11 or more attorneys, whereas Kansas placed 20.2%, Oklahoma placed 20.9%, Arkansas placed 21.7%, Colorado placed 24.2%, all in said categorization, and Texas placed 25.6% of its class in firms of 500 or more alone.

Under Law School Transparency's Employment Score method (which justifiably excludes solo practitioners), Washburn ranks 107th in the country. So it appears that Washburn is using its solo numbers to inflate its employment rate over clearly superior schools when calculating its "24th in the country!" claim.

Lately, law schools have been hiding behind the "our representations were technically true!" fortification - which is somehow abutting the "our representations were so absurd no one would believe them!" fortification - in response to the lawsuits that gained almost no traction.

But what is it when a school apparently counts solo practitioners as "employed" or in a "position," much less one that is long term? Is that even technically true? A solo practitioner isn't employed or holding a "position," and I would bet that most don't last more than a few years before doing something else. A solo practitioner is an entrepreneur at an uncertain start-up, almost always carrying additional business debt and negative operating costs until business picks up and large up-front expenses can be paid down. To compare it to an associate position in a firm of 20+ attorneys is disingenuous, at a minimum.

The data is pretty clear that prospective law students generally don't want to be solo practitioners immediately if they have a choice, and solo practice for new graduates is likely a symptom of low employment prospects rather than any conscious expression of being "ready to practice."

The following chart shows the percentage of recent graduates going solo versus the median LSAT score of the school's most recent incoming class. (Lincoln Memorial and the Puerto Rican schools were excluded.)

Monday, October 12, 2015

Who wants to be a lousy fiction writer?: A review of Drexel Law Prof. Lisa McElroy's new law school novel "Called On."

Seven reviews on Amazon as of this writing, and all seven gave "Called On" the highest possible rating of five stars (though at least three of the ratings are from McElroy’s fellow law professors). So perhaps I am all alone in my opinion that this book is crap. Scribblers like David Lodge and Francine Prose have written novels satirizing academia, but neither has scored anything close to unanimous five star ratings on Amazon. True, McElroy may not shine when it comes to crafting compelling narrative or memorable three-dimensional characters, but she is unparalleled in generating cutesy witticisms about (as one of the five star reviews puts it) "life, love, and the law."

"Called On" is the story of an idealistic young One-L at elite Warren Law School named Libby Behl and her quest for love and legal wisdom. It is also the story of Connie Shun, the brilliant, good-hearted, strong, perceptive, down-to-earth, endearing, and witty M&M-loving (that's M&M, not S&M) law professor who mentors and inspires Libby. (I wonder who Connie Shun could possibly have been based on).

Even though the author actually is a law professor, this novel is still badly misplaced. It should have been set instead in a high school or a summer camp. The story has a teen lit vibe, and all the characters speak and emote about "life, love, and the law" like angsty or stuck-up adolescents.

"Um, hi. I’m Libby. Just wanted to plug in my laptop? Looks like we’re in for a long hour or so."

The woman pushed her glasses up on her head.

"Sorry. Need the plugs. Taping and typing, that’s my technique. Law review. Order of the Coif. Supreme Court clerkship. Every little bit helps. Early bird gets the worm and all that."

Libby laughed. This woman couldn’t be serious. Law school was about saving the northern spotted owl (OK, so Libby was about two decades late for that one), standing up for marriage equality (and about a year late for that one, at least in part), and fighting for equal pay for women (never too late).

* * *

Libby didn’t want to lose her cool. But seriously?

"Yeah, so, don’t you think it’s fair for us all to be on the same playing field?"

The woman put her glasses back on her nose. "We are. We can all get here early. And use the plugs we need. And those who don’t should just realize that they aren’t cut out to be federal appeals court judges."

McElroy, Lisa (2015-09-18). Called On (Kindle Locations 160-165, 168-172). Quid Pro Books. Kindle Edition.Looks seriously bad for poor idealistic Libby-- arrayed against such a ruthless competitor, like an overly-compassionate worm on the same playing field as an early bird. And things go from bad to mortifying when Libby spills a cup of coffee near the lectern, causing Professor Connie Shun to slip and fall to the ground as soon as she walks into the classroom. Talk about a disastrous start to law school!

But the formidable professor keeps her composure. ("If Justice O’Connor had fallen in a pool of coffee, this is how she’d look. Together. In the least together situation ever.") Shun gets right back up on her feet and conducts a virtuoso class, even without her coffee-spoiled notes, using mistakes in sports officiating to illuminate how law and justice are not necessarily the same thing. Libby redeems herself too. She is "called on" in class, her worst fear realized, but meets the challenge with aplomb by out-arguing fellow student Anderson Kraft, the suave and handsome Harvard T-shirt-wearing guy with the cocky attitude, who turns out to be the villain of the novel.

Indeed, it is not long before the worthy underdog triumphs and the arrogant are humbled. Professor Connie Shun’s pedagogy, in its critical and humanistic depth, guides students toward an understanding that law and justice, though different in nature, do not merely intersect or diverge, but can actually propel each other. Because Libby has a "calling" to use the law to do good, she is able to grasp this profound concept, which eludes the more self-centered or shallow students, one of whom ponders that, "Every ILT class was the same. They talked about law blah blah blah and justice blah blah blah and absolutely nothing that would ever help [him] do a deal or draw up a contract when he was a lawyer someday."

"Connie sat and watched. For all the crap law school had been taking in the media lately, this was the kind of class discussion that proved all the "law school is a scam" bloggers wrong. She didn’t have to do anything but get the students started with a provocative question. Then they took over."

McElroy, Lisa (2015-09-18). Called On (Kindle Locations 322-324)Libby may suffer from bouts of self-doubt, but perceptive Professor Shun almost immediately identifies her as a future legal star. "The best ones — the ones Connie took under her wing — were always about more than wanting a prestigious career and beaucoup bucks. They were about solving major problems in the world."